Rejected! The Marriage Proposals that Didn't Make the Cut

A primer for rejected proposals in 'Pride & Prejudice' & 'Emma.'

Later this week, I’ll be sharing an essay that looks at rejected marriage proposals in P&P & Emma. This piece specifically focuses on Jane Austen’s critique of a society that forces a woman to say yes to the first marriage proposal she receives, for she could never be certain that a second offer would be made to her. Rejecting a proposal in the Regency era could also damage the reputations of the man & the woman.1

In Austen’s novels, we encounter women who feel compelled to marry in order to avoid poverty & other perils of spinsterhood. But according to the rules of Regency courtship, they had to wait to be asked & were expected to express gratitude for the compliment of a proposal.

Austen gives two of her strongest heroines, Elizabeth Bennet & Emma Woodhouse, agency to question why a woman should accept a marriage proposal merely because she is asked. Lizzy & Emma could only be persuaded to marry a man they respect & love.

To help guide you through the essay (especially if it’s been a minute since you’ve read P&P & Emma), I’ve put together this primer on the rejected proposals I’ll be discussing.

Things to know:

Elizabeth Bennet & Emma Woodhouse each reject two proposals in their novels.

The rejected proposal scenes in Emma are particularly complex, as they’re the result of Emma’s matchmaking.

I’ve tried to highlight—in a screenshot—why each proposal was rejected, but there will be more context in this week’s essay.

This proposal is an example of “nonconsensual consent”

While Mr. Collins’s proposal to Elizabeth in P&P was “by the book,”2 proposing to a woman after a week’s acquaintance might have been too hasty even by 18th-century courtship standards. But finding a wife was Mr. Collins’s “design” for visiting Longbourn, & he was happy to find that the Bennet sisters were as hot as people said they were.

Elizabeth is actually Mr. Collins’s second choice—he wanted Jane, but Mrs. Bennet directed his attention to Lizzy because she’s basically the same, & Jane was expected to receive a proposal from Mr. Bingley. Mr. Collins agrees that Elizabeth is practically Jane’s equal; he even references this in his proposal: “Almost as soon as I entered the house I singled you out as the companion of my future life”3 (emphasis my own).

What’s most infuriating about his proposal is that he takes Lizzy’s no as a yes, what Heather Nelson calls “nonconsensual consent.”4 Mr. Collins doesn’t take Elizabeth’s refusal seriously, laughing it off as some little game she’s playing to entice him. In his eyes, Elizabeth has no power to refuse his offer—her father’s estate is entailed to him, & she has little more than her charms to recommend her to another suitor.

Mr. Collins wants to have power over his wife. He wants to be the Lady Catherine de Bourgh in a marriage.

This proposal says, “I’m pathetic & only looking to enrich myself”

Mr. Elton, vicar to Highbury, is a social climber who’s interested in Emma for her fortune & status in the community. He seizes the opportunity of being alone with Miss Woodhouse in a carriage (no escape!) to propose, telling her he’ll die if she refuses him.

This insensible, over-the-top speech makes no waves with Emma. After all, she was only being nice to Mr. Elton because she thought he was in love with Harriet; if she had any idea that he believed he had a shot with her, she would have put a stop to his frequent trips to Hartfield.

The biggest flaw in Mr. Elton’s proposal? He flatters himself that Emma could not refuse him. Emma can detect this presumption in his manner, but she’s too concerned about how she’s going to break this to Harriet to dwell on how pathetic he is.

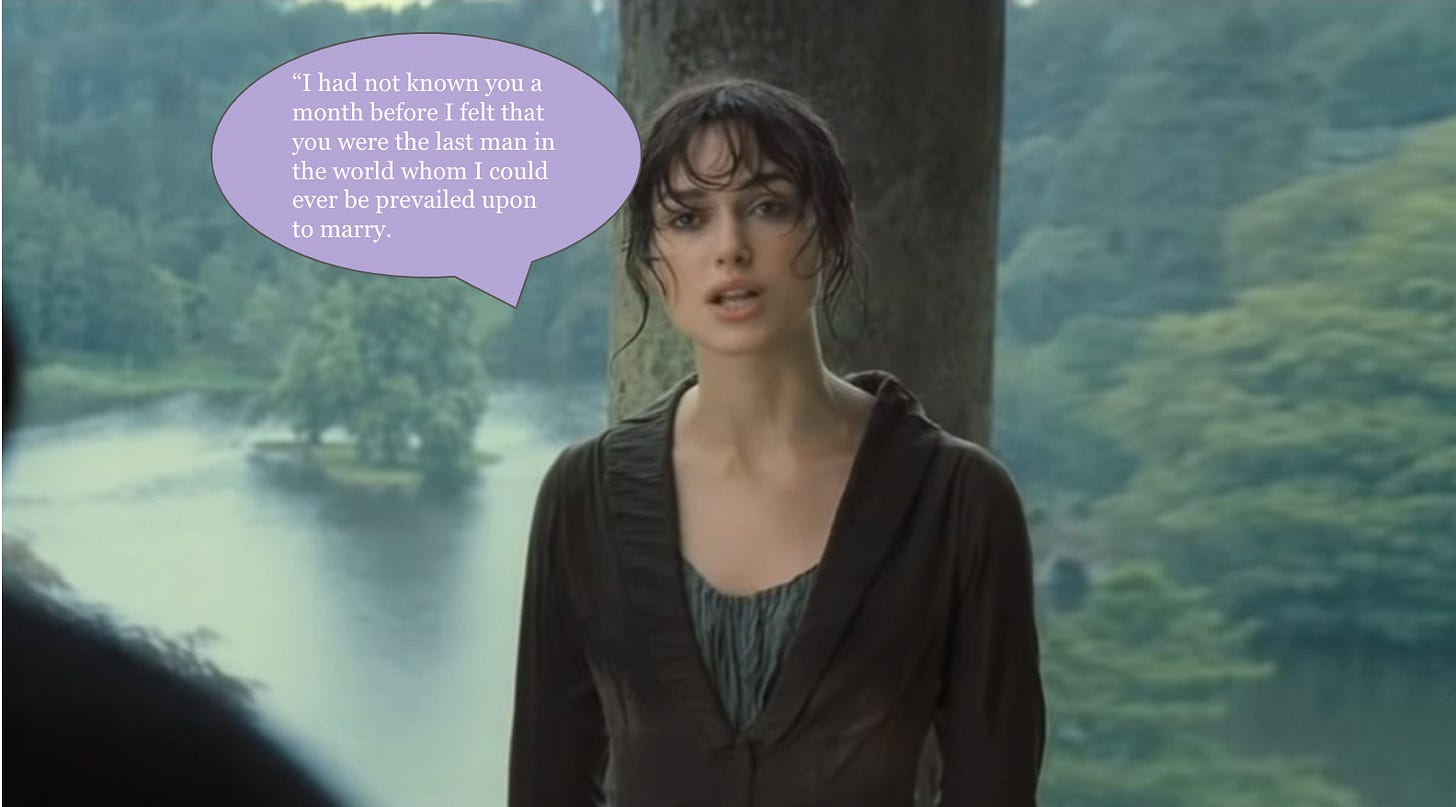

This proposal is just insulting

Mr. Darcy has a lot to offer: £10,000 a year, the beautiful grounds of Pemberley. Elizabeth must find his proposal a compliment…except that he insults her & her relations. Perhaps Mr. Darcy thinks Lizzy would find it romantic that he’s willing to risk the happiness of his family to marry her.

She does not. She has her reasons to hate his pride, to despise him for all eternity, & telling her how ardently he admires & loves her doesn’t change that.

This proposal is a letter only Harriet & Emma get to read

Mr. Robert Martin—a farmer—has proposed to Harriet Smith in a letter! While Harriet is the only person intended to read this letter, she can’t decide if it’s a good proposal; she must bring it to Emma!

Ironically, we must rely on Emma, too, since we’re not allowed to read the letter. The last thing Emma wants is to see Harriet married to a farmer, but the narrative voice conveys what she really thinks about Mr. Martin’s proposal: “There were not merely no grammatical errors, but as a composition it would not have disgraced a gentleman; the language, though plain, was strong & unaffected, & the sentiments it conveyed very much to the credit of the writer.”5

It’s not just that Emma thinks it’s a good proposal—she can’t even follow through with her lie that one of Mr. Martin’s sisters must have written it for him: “I can hardly imagine the young man whom I saw talking with you the other day could express himself so well, if left quite to his own powers, & yet it is not the style of a woman; no, certainly, it is too strong & concise; not diffuse enough for a woman.”6

Emma must use a different tactic to encourage Harriet to refuse him. She uses the fact that Harriet came to her for advice as evidence that Robert Martin’s proposal couldn’t possibly be accepted.

Ultimately, Emma points out, their friendship is saved when Harriet says (hesitantly) that she shall refuse him. Thus, Emma rejects a perfectly good proposal on behalf of her very dear friend.

Stay tuned: I’ll be sending out my essay “A Proposal No Woman Could Refuse…or Could She? Rejected Proposals in Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice & Emma“ later this week.

“While a young woman could refuse an offer of marriage—not really considered a good idea, mind you, but it was possible—she could easily acquire a reputation for being a jilt for doing so. In fact, both parties could be damaged by a refused offer of marriage, so matters were to be handled with the utmost delicacy and consideration for the feelings of the young man.” See “By the Book: Mr. Collins’s Proposal” by Maria Grace (Jan. 10, 2017).

See “By the Book: Mr. Collins’s Proposal” by Maria Grace (Jan. 10, 2017).

See Pride & Prejudice by Jane Austen (1813), Volume I, Chapter XIX, p. 103.

“Austen shows that nonconsensual consent only becomes legitimate consent when men progressively reform on gender equality & women initiate more consent opportunities. Pride & Prejudice least presents the tantalizing possibility to female readers that they could consent or dissent & (eventually) arise victoriously, custom be damned. In that way, Austen anticipated modern consent theory.” See “Elizabeth Bennet’s Proposal Scenes & Nonconsensual Consent” by Heather Nelson (2020), Persuasions, No. 42, p. 196.

See Emma by Jane Austen (1815), Volume I, Chapter VII, p. 50.

See Emma by Jane Austen (1815), Volume I, Chapter VII, p. 50.