Jane Austen Fans Feel "Seen" (Called Out?) by Greta Gerwig's 'Barbie'

What it means to be a woman & a fan.

Since Greta Gerwig’s Barbie hit theatres on July 21st & has become the highest-grossing film directed by a woman, Jane Austen fans have been speaking out about its reference to the 1995 BBC adaptation of Pride & Prejudice.

After Stereotypical Barbie (Margot Robbie) fails to fix the rift between Barbieland & the Real World, allowing Ken (Ryan Gosling) to tell the other Kens about patriarchy (Barbieland, you probably guessed, is meant to represent a matriarchy) & turn Barbieland into Kendomland, Barbie decides she can’t fight what’s happened & might as well accept her fate of getting flat feet & cellulite. As she plants herself facedown into the plastic lawn of her Barbie Dream House to cry about this unexpected turn her perfect life has taken, a commercial for Depression Barbie (like Stereotypical Barbie but with smeared mascara) interrupts the scene like a breaking news flash: This Barbie will eat an entire package of Starbursts while scrolling through an estranged friend’s engagement photos on Instagram, & binge watch the six-episode BBC miniseries of P&P, starring Jennifer Ehle & Colin Firth.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

If you’re a Modern Austen reader, you’ve probably spent many weekends alone, feeling your feelings through this Austen adaptation. Who among us hasn’t sought comfort in watching Mrs. Bennet try to marry off her five daughters or skip ahead to the scenes where Colin Firth’s Mr. Darcy stares intensely & admiringly at Lizzy? Swoon! Gerwig’s choice to make binge watching P&P a feature of Depression Barbie either shows that she’s at least aware this is a thing, or that she’s one of us;—I’d like to think it’s the latter.

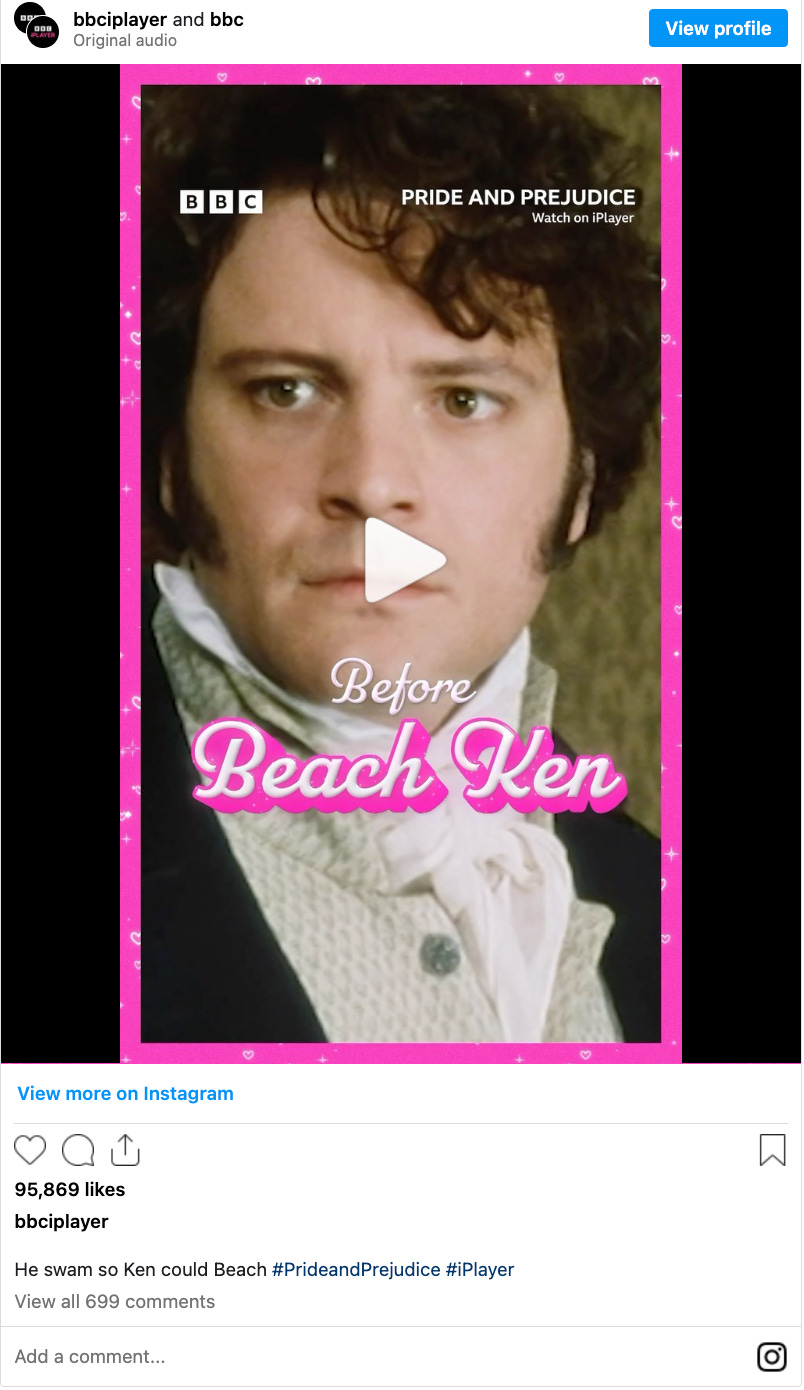

The Jane Austen fan circles I follow online exploded with excitement over this scene in Barbie—most groups unanimously declare the 1995 version to be the best P&P adaptation (Joe Wright’s 2005 adaptation can go drown in Mr. Darcy’s lake) & love spotting references out in the wild. I saw a lot of posts from fans who felt seen by Greta Gerwig.

The BBC even had a response to Gerwig’s little joke.

While the Jane Austen online universe doesn’t seem to find the film’s reference to using the 1995 P&P as a coping mechanism mean-spirited, some fans had to wonder if Gerwig might, perhaps, be calling them out.

Now that I’ve seen Barbie three times, I’ve noticed that my reaction to the Depression Barbie commercial changed with each viewing; I always laughed, but not for the same reason. The first time, I was laughing at a type of Jane Austen fan who I like to think I’m not—one who loves Austen for the romance & Regency manners & balls, or primarily watches the 1995 P&P to see Colin Firth walking out of a lake in a wet shirt. This is the type of fan who doesn’t appreciate Austen’s contributions to literature & views Mr. Darcy as a romantic hero (let’s be real: the only reason to love Darcy is that he loves Lizzy Bennet). The second time, my laugh had an uncomfortable undertone, because I do put on an episode of P&P whenever I want to watch something familiar, & I’ve certainly watched the BBC adaptation more times than I’ve read the book from beginning to end.—Is Greta Gerwig calling me out?

But this last time I watched Barbie, I could laugh at myself (like Lizzy would) during the Depression Barbie commercial because Gerwig is inviting us all to laugh at the ways we cope with modern life by applying them as features to a doll that’s meant to represent the idea of a perfect woman. Then Mattel can turn these ideas into a profit.

The film’s reference to binge watching P&P & not just any show on Netflix resonates with its overall message. Like Barbie, Jane Austen is for women. She’s often dismissed by men like Ken as an author who writes about women’s issues: Marriage, manners, & falling in love. Never mind that Austen wrote about these things because women have always had to care about them. In Austen’s time (& not much has changed today), women had to think about how they would make their way in the world in a way that men never have—that’s why women get Austen. Of course there are men who believe that Jane Austen deserves to be read as seriously as Shakespeare, but she’ll likely never shake the label “writer of women’s issues.”

I sometimes wonder if it’s the world of Jane Austen fandom that contributes most to this perception. All the festivals, all the adaptations, do they give the impression that Austen invented the Regency romance novel & shouldn’t be taken seriously? No—I’m allowing patriarchy to warp how I think! There must be just as many Shakespeare adaptations & festivals, but fans of the Bard aren’t branded as silly, hopeless romantics. Jane Austen’s perception is not the fault of the author or her fans, but the systems of patriarchy & capitalism, which force us to box ourselves up into genders & the culture we consume into genres. If Jane Austen fans feel called out by Greta Gerwig’s Depression Barbie, it’s because they’re used to being called out for the movies & music & books they enjoy, especially for comfort.

I often feel the need to explain why I love Jane Austen when I talk about her novels or this project to men, & I don’t mean the way one of the Kens explains the importance of The Godfather to President Barbie. It’s more that I need to defend my reasons for liking Austen, which may be an unfair assumption on my part—perhaps more men are willing to read P&P or watch the 1995 series than I think. There are, after all, Jane Austen scholars who are men, & I’m actually more concerned with proving I’m a serious reader of Austen than making the case to take Austen seriously.

I’m afraid of being labeled a certain type of Jane Austen fan. The type I was keen to laugh at when I first watched Barbie, the type my Principles of Literary Studies professor (a man) certainly wouldn’t approve of. In some ways I’m glad that it was a male academic who introduced me to P&P; I’ve now gone through the process of internalizing his perspective, then rejecting it with each re-read. My professor couldn’t forgive Charlotte Lucas’s choice of husband, blindly loved Lizzy (which is fair), & understood the marriage plot to symbolize a moral code Austen was creating without acknowledging that it was also a lived experience for many women in 18th- & 19th-century England. To him, women in P&P were either silly (Lydia), catty (Miss Bingley), or sensible (Lizzy), aligning with the trope of fiction that women can only be one thing. In Barbie, Gerwig explores the harmful effects of a world that allows individual Barbies to only be stereotypical or president or an astronaut, & Ken to only be beach: When faced with a dilemma, they feel no responsibility to solve it.

When Jane Austen is taught in an academic setting, it’s often from the perspective of a man, & I feel this is where my tendency to categorize & judge Jane Austen fans comes from. I’ve been taught to approach Austen seriously, academically. Yet I can’t help imagining her as an agony aunt & how she might advise modern heroines on their modern quandaries; nor can I help turning to the 1995 BBC adaptation of P&P for comfort when I’m lonely, stressed, or a little bit sad. I turn to P&P for comfort knowing full well there’s nothing comforting in it. Or, rather, that any comfort I feel is the trick of Austen, who paints a very insular world where danger to a woman & her reputation lurks around every corner. (And sometimes I do watch it to see Colin Firth emerge soaking wet from a lake.) This doesn’t mean I take Jane Austen’s work any less seriously or that I need disdain fans who have no wish to approach her work academically. There are many ways to enjoy Jane Austen, & all are valid. Both Jane & Greta, I believe, would agree.

In Barbie, Greta Gerwig isn’t calling out depressed Jane Austen fans—she’s calling us all out for the ways we ignore, cope with, & cover up our problems. She’s making a joke about how this seems to be a feature of the human condition, not a bug. Her P&P reference, perhaps, is merely a nod from a fellow fan who also finds comfort in watching Mr. Darcy fall in love with Elizabeth Bennet.